In his short book The Weird and the Eerie, the British writer Mark Fisher lays out the borders of the title’s terms. The weird, he writes, demarcates “the presence of that which does not belong.” By contrast, the eerie is “something present where there should be nothing.” Phenomena as puzzling as this is what Richard Mosse documents in his discomforting The Castle: photographs, taken with a thermographic camera, of refugee camps and key border crossings along migration routes into Europe from the Middle East, Central Asia and parts of Africa.

In his work, Fisher pinpoints the critical issue of agency: where there should be nothing, who is putting in place what doesn’t belong there? And if this sounds a little Kafkaesque, that’s because it is; Mosse’s title consciously evokes Kafka’s The Castle, a poignant tale of a hopeless struggle for respect and recognition by a man known only as K. In the village where K arrives, he tries to make meaningful contact with the castle, the mysterious source of authority, but the bureaucracy defeats him.

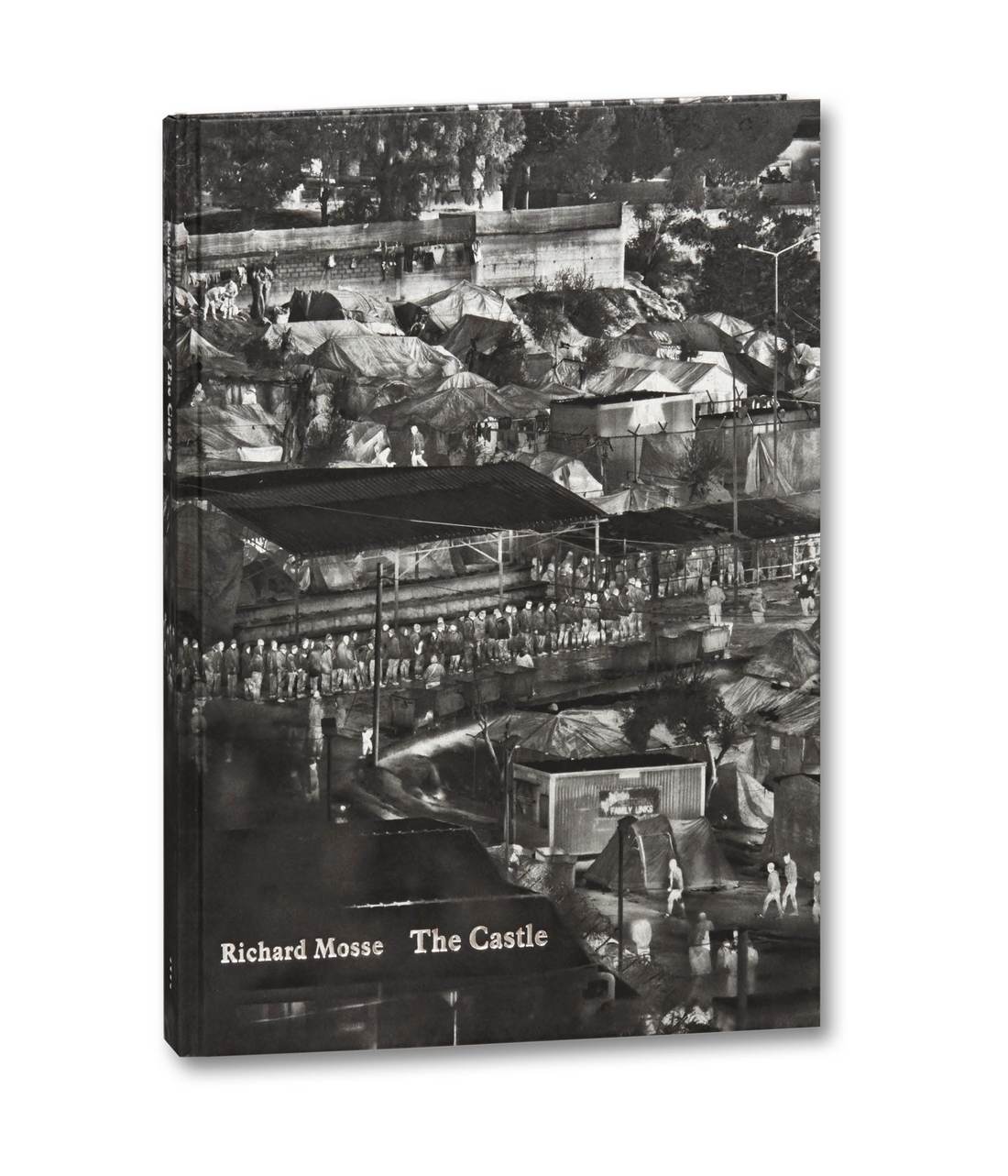

Thermographic cameras, sensitive to heat from human bodies rather than light, are used for long-range surveillance and the policing of borders. When allied to weapons systems, they can assist with lethal intent in tracing and targeting their quarry, as detailed by one of the book’s four texts—an essay tracing the genealogy of this type of photography written by Paul K. Saint Amour. Mosse retools this camera technology, self-reflexively and with subversive intent. He supplants conventional images of dispossessed refugees—usually represented with a humanistic eye—by depicting them as spectral presences in a peculiar landscape of half-recognizable built environments.

The Castle is a work of somatic surveillance designed to disorientate, visually and cognitively. Individuals and groups are rendered as white shapes, ghostly hallucinations where faces become bleached masks. The pictorial perplexity this creates indicates not some breakdown in the neural system, or some otherworldly experience, but a disconnect at the societal level. The nocturnal ambience that inhabits the daytime photographs conveys the sense that something is fundamentally not right here.

The scenes in Mosse’s work are cultural hauntings, registering a failure to transfer loss and disruption into something the psyche can deal with in a normal process of mourning and recovery. The human figures in the photographs are not ghosts but premonitions; signs of an administered world and its instrumental reason, one where the subject is reduced to bare existence. But if this sounds a little abstract or theoretical, one only has to look closely at details in the pictures.

The book’s photos unfold in a series of spreads and, on the outside of the flaps that enclose them, there are enlargements of details from the depicted scene. Early on, there is an image of the Greek-Macedonia border in March 2016 after Macedonia closed its borders to all asylum seekers. The left flap amplifies two people that are moving away from the tents of a makeshift camp. The figures’ poses and posture evoke paintings of Adam and Eve—and John Milton’s description of them in Paradise Lost “with wandering steps and slow”—walking arm in arm into exile after their expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

The extent of the crisis that Mosse documents can be gleaned from the range of countries covered in his project: not just the Balkans and eastern Mediterranean but also Italy, Germany, Lebanon and France. There is a panoptic shot at Berlin’s Tempelhof airport as a temporary shelter in 2016, eight years after its closure. The viewer peers down to see inside the terminal building, as if into a doll’s house with the roof taken off, to observe the refugees’ domestic quarters. The feeling of intrusiveness that comes from looking at their bunk beds and bags of meagre belongings registers the fact that people are living here in a state of semi-permanence, transit passengers in the extreme.

Something similar is evoked in the picture of a stadium in Greece, abandoned after the 2004 Olympics. We see items of clothing suspended from an improvised washing line, a family sharing a picnic in the foreground and, high above them in one of the tiered rows of seating, a solitary ‘spectator’ sits waiting, as if for Godot. Mosse photographs a camp at Ventimiglia in Italy, where refugees from Africa attempt to cross the border into France. A 2018 Oxfam report accused French border police of detaining minors without food or water, cutting off the soles of their shoes and removing phones’ sim cards before illegally returning the refugees to Italy.

What comes across in photographs like the one taken at Ventimiglia is the sense that the camps are less like an ark, that encloses for ultimate salvation, and more like a zoo that detains in order to satisfy the needs of others. As Fisher pointed out in regard to the weird and the eerie, there is the question of agency—responsibility for “the presence of that which does not belong” and “something present where there should be nothing.”

The monochrome, panoramic pictures that provoke these questions are not produced in one click of a shutter. A painstaking and manual process makes a composite from a multitude of square images and the end result is a single thermograph. Turning the pages of The Castle, what you see are the results of a focused, prolonged and somewhat heartbreaking act of looking.