In the very centre of Aperture’s new 236-page Ming Smith monograph readers will find a small flurry of the American photographer’s intimate self-portraits. In one of these images, Smith photographs herself laying down in a green velvet dress and clasping a pink, orchid-like flower in her hand. In another, she dons a midnight blue ball gown and diamonds, and poses herself in front of a shimmering plastic background, eyes averted coyly from the camera. And after both of these images, in a subversive twist, she even includes an old Revlon beauty advert she appeared in as a model in 1975.

Themes of Black femininity, beauty and dignity have always been important to Smith—both as a photographer, and as a woman—and she has often rallied against the aestheticization and objectification of Black women. Placed together, these pictures are a tacit reminder of that fact, and after pages and pages of the photographer’s iconic 1970s jazz scene portraits, and her social documentary work, they are a powerful interlude within the edit. They show us Smith’s talent not just for staging photographs, but being in them too. And, more importantly, they show us that in figuring out how she wanted to depict her sitters, she started with herself first and then worked her way outwards. That’s such a rare and refreshing way for a photographer to work.

A treasure trove of highlights and unseen moments from the artist’s career, this new monograph comes four decades after Smith began taking pictures. Born in Detroit in the 1950s, Smith has grown used to being a person of firsts across the years. As a young girl, her family was one of the first black families to move into a white neighbourhood in Columbus, Ohio. Later, after moving to New York to pursue a career as a model and artist, she became the first female member of the legendary Kamoinge Workshop for Black Photographers, founded by Roy DeCarava. And after this, she went on to be the first Black woman photographer to have her work acquired for the MoMA’s permanent collection. It’s said that when she first turned up to the museum with her work back then, the receptionist assumed she was the courier.

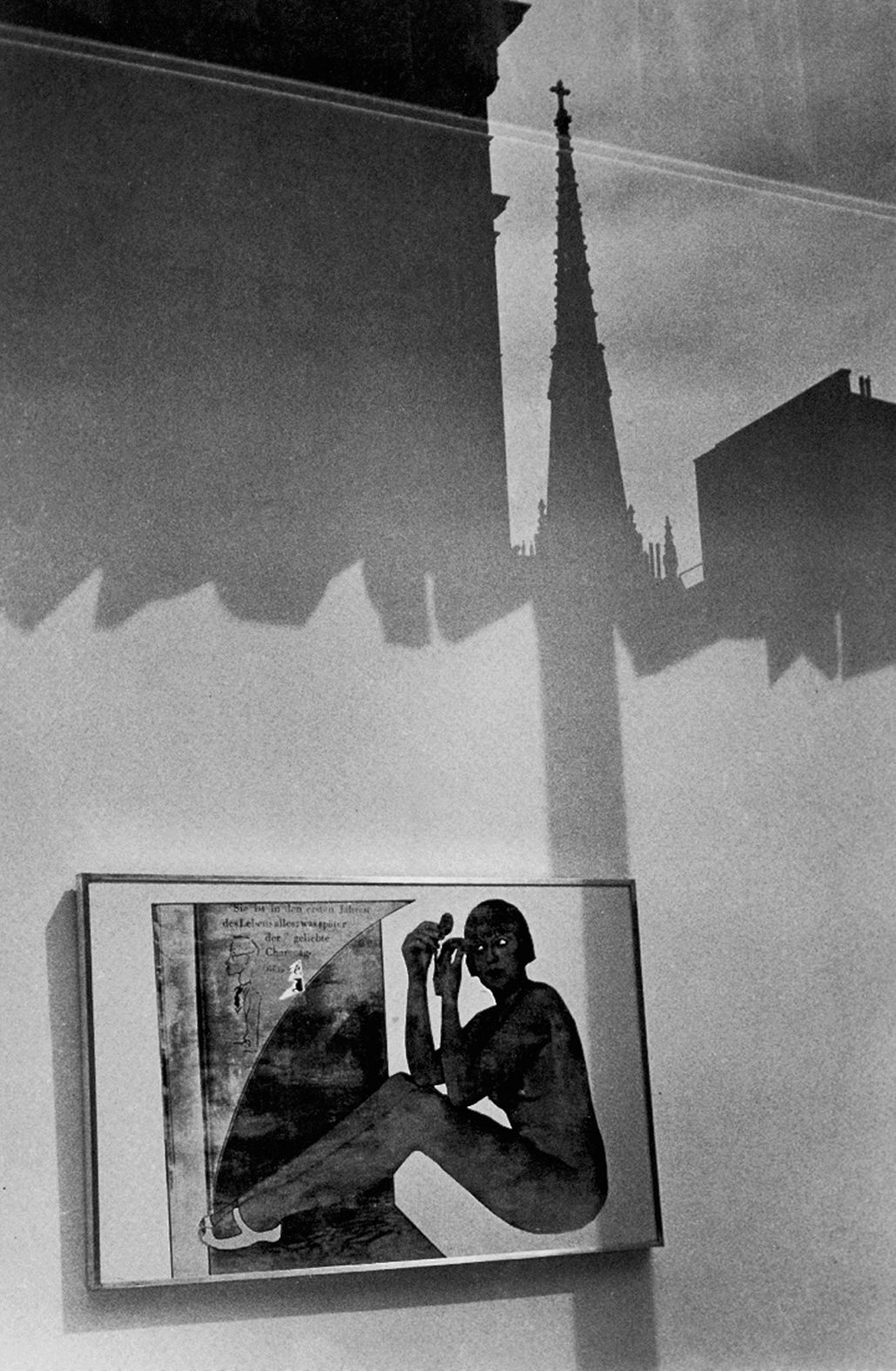

One of the first things you’ll notice about this book is the shadows. Silhouettes and spectres—of both people and places—haunt the pages here, and often, Smith’s photographs are blurry, grainy or hazy depictions of the things she placed in front of her lens. Through the various contributor texts included in the publication, we learn that this style of photography was one subsumed into Smith’s process for a very specific and sensitive reason. In The Sound She Saw—a conversation between writer, musician and producer Greg Tate and artist Arthur Jafa—Tate says in his introduction, “Smith’s strategic deployment of blurring in rendering her varied Black subjects and communities is seen by Jafa as an act of love and loving protection from predation by a policing white gaze.”

Elsewhere, Jafa says that you can’t really confidently identify anyone in Smith’s pictures because, consciously or not, she embraces “techniques that, in a sense, void the ability of the photograph to function as evidence”. The truth of this statement lives in the pages of this book. We can see it in images such as those of jazz legend Sun Ra. In one of the book’s most impactful pictures, printed across a double page spread, Sun Ra is blurred almost to abstraction, but it’s absolutely him. The shimmering presence of it as a photograph just tells us so. To be able to distill the essence of a person’s being—so that we know its them, even if we can’t quite see it is—is remarkable, and it happens time and time again in Smith’s work. Pictures of musicians and dancers proliferate here; opening the book with a lyrical, rhythmic sort of energy.

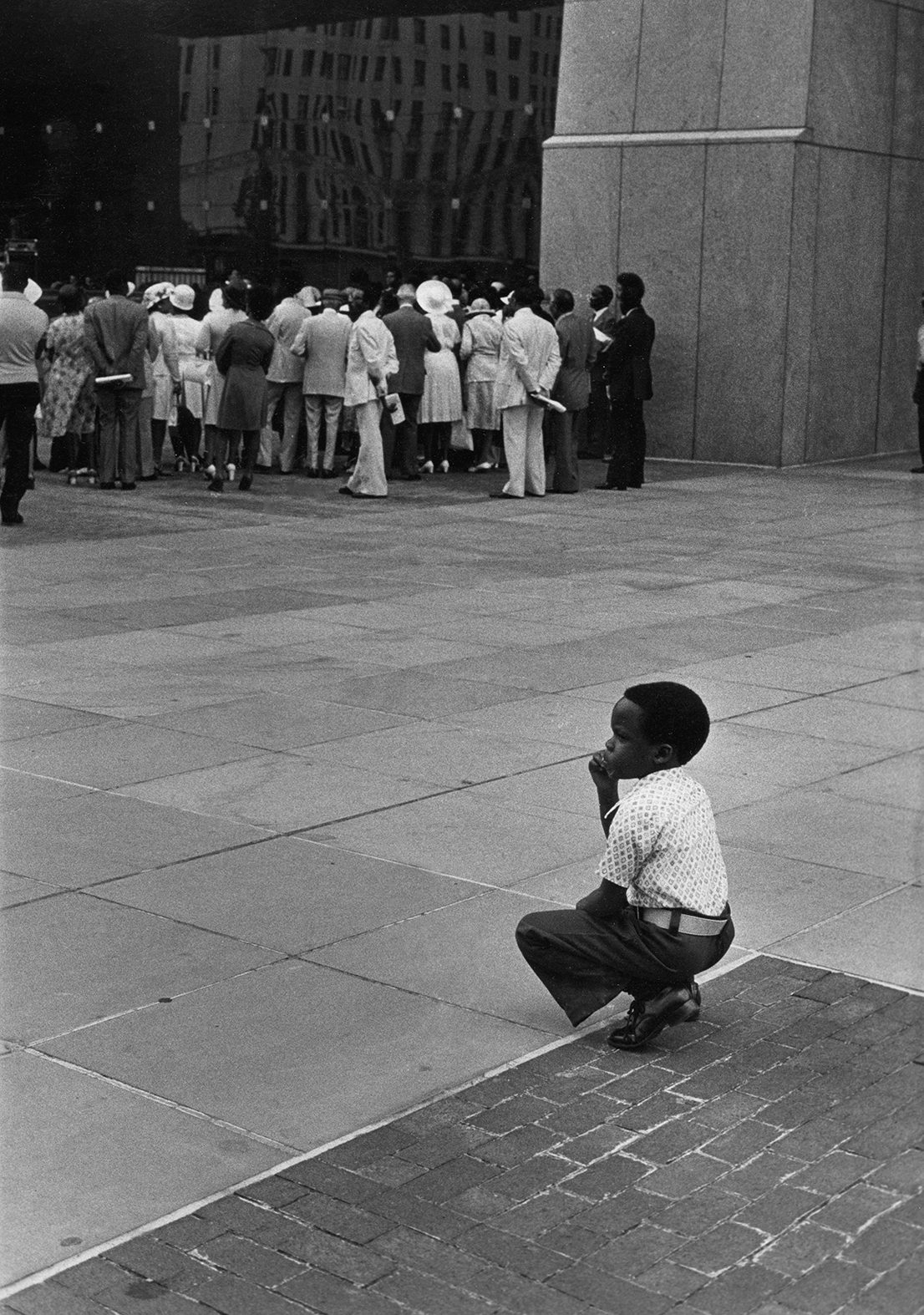

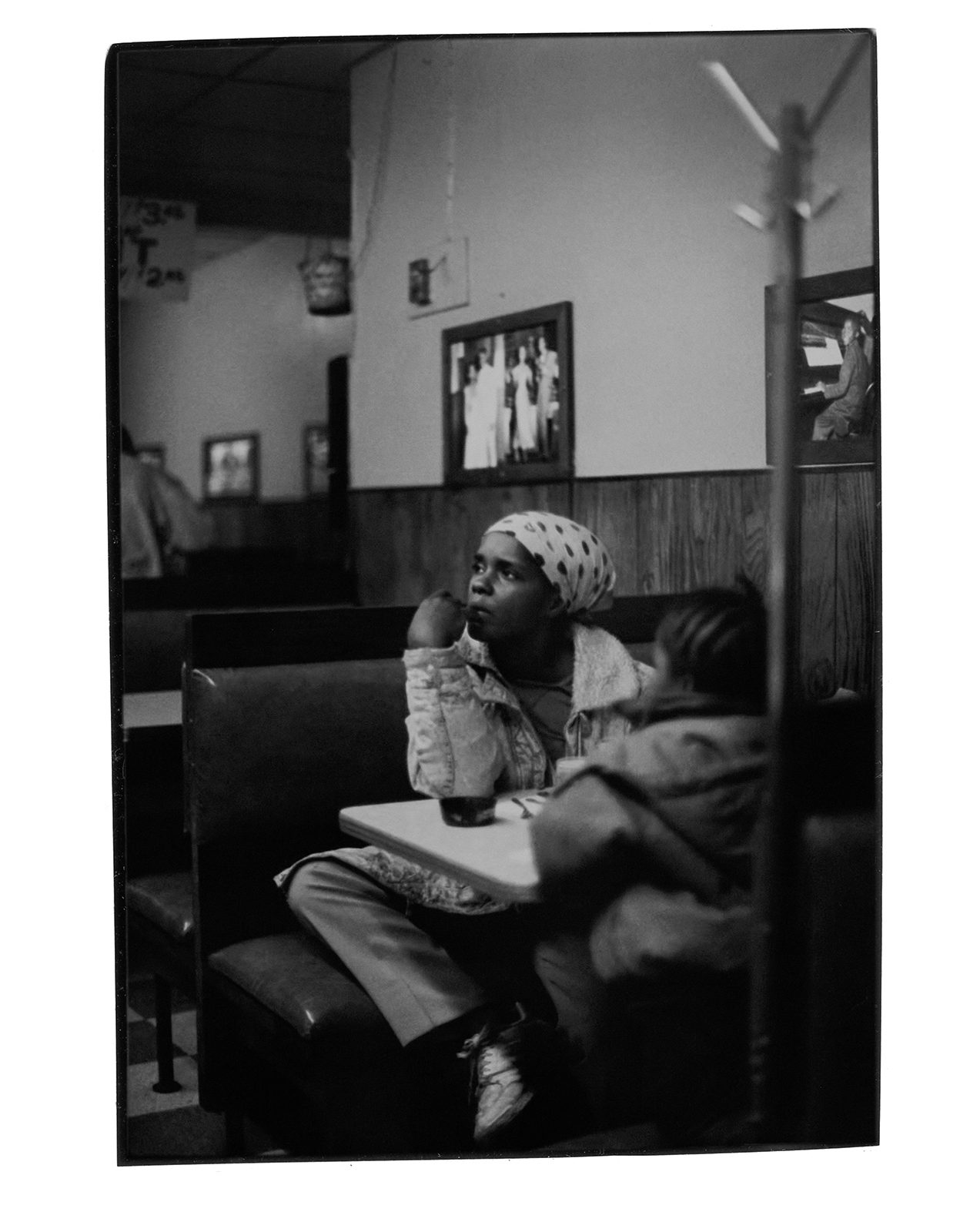

In the half of the book after Smith’s self-portraits, her street photography really takes centre stage. Beginning quietly, they unfold every now and then into images of parades and youth marches, church congregations and Sunday services, funerals and family meet-ups. It’s as if the book gains momentum, and offers us pictures that explore the fundamental power of gathering, communion, and of what it meant for the people Smith spent her life photographing to gather in Black spaces.

Where did Smith learn to see the world the way she does? As I look back through the book, I realize that the essential clue to the answer of this question is actually given to us in one of the very first images we come across. In it, a small window is opened into a shadowy room, and its surface reflects the street outside. Taken in 1979, Smith called the picture The Window Overlooking Wheatland Street Was My First Dreaming Place—it was her childhood bedroom. What must she have witnessed from that window. What magical, everyday situations must have sparked before her eyes. What things must she have dreamed about for her future. As if to echo the importance of this picture, the two final images in the book are of windows too—one of Ming looking out of the window on her first trip to New York in 1959, and one of a square of light that a window throws across a doorway.

In amongst the shadows, Smith has always looked for light, and as a result, the people she has photographed across the decades glow within this book; illuminated in even the darkest of spaces. For all this time, her mission has been to conjure dream spaces out of reality, and the richness of her oeuvre, presented to us here, proves her success. In the end, this volume becomes a testament to a groundbreaking career, revealing the slow, shimmering emergence of a visual style created entirely for the celebration and future preservation of Black stories, spaces and lives.