The word ‘dichotomy’ is a curious and complex one. Deriving from ancient Greek, its essential meaning is ‘from two, apart’, which makes it, by its very nature, something of a paradox—denoting both incongruity and duality all at once. In the world of botany, the process of dichotomy denotes a constant forking, or a perpetual changing through growth, like in the veins of leaves. In astronomy, dichotomy is the phase of the moon when half of it is invisible. The main dictionary definition of the word is ‘division into two mutually exclusive, opposed, or contradictory groups’, but what if that division happens within one person? Related words such as ‘invisible’ or ‘apart’ are not so easy or appropriate to use.

For 22-year-old photographer Kymara Akinpelumi, dichotomy is more than just a word—it’s a state of being, and a way of life around which her series Dichotomy is based. Born in 1999 in the north of England, Akinpelumi is of dual heritage, and this fact is the main source of inspiration for her work. “This idea of being both black and white, is something that people find hard to digest,” she says. “Whilst experiencing some harsh racial oppressions, I can also recognize my white privilege. This has brought on difficulties of knowing where to place myself in the world when it’s so often split.” The title of the work and the word dichotomy is therefore “less of a statement and more of a question,” she says. A way of considering her lived experience and reaching out to others like her.

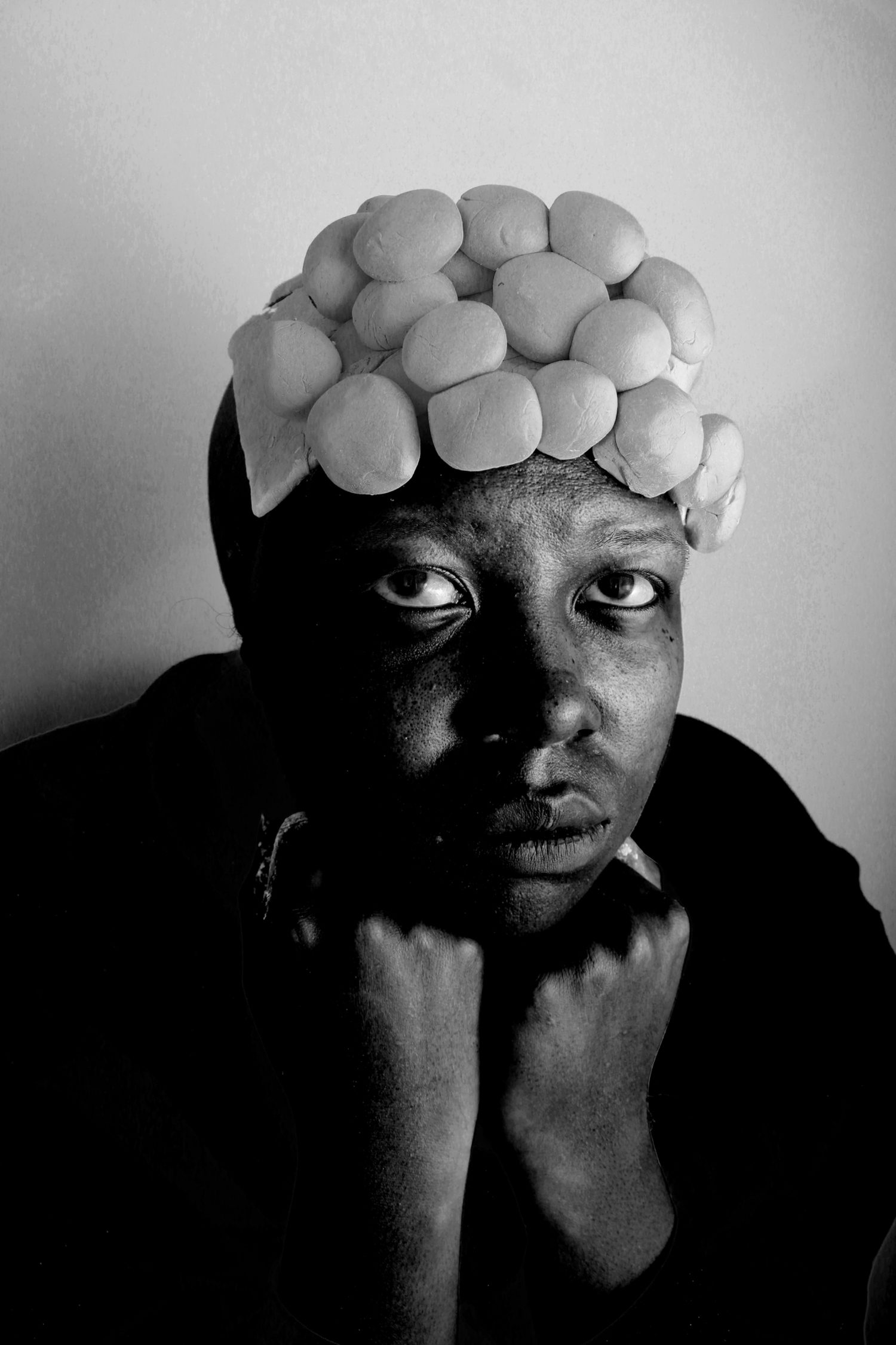

Shot in black and white and framed as striking head-and-shoulders portraits, all of the images in Dichotomy are self-portraits—ones made by the photographer setting up a timer on her camera. All of the photographs come with captions that detail little stories from Akinpelumi’s past. Her images are often loaded with symbolic meaning and the objects she chooses often have a broader racial history to them that she then links to a personal memory.

She points out the use of long beads that resemble Double-Dutch ropes in one of her images as an example—a sport and a term that has become an essential piece of black culture across the years. “This was really fun for me to return to because I used to love skipping. It just goes to show how the small things can make a real difference in decolonizing the curriculum whether that’s a lesson or a sport, putting people in a position where their history is celebrated is so important. I’m 22 and I still remember the feeling.”

For some of the photographs, she fashioned sculptural headpieces from white clay— a choice she made because it’s a material she could manipulate easily, but also for its nostalgic connotations. “It made me feel like the child that I was returning to,” she says thoughtfully. “Often when you feel as though you don’t belong to a place, you create one for yourself. I made my own space within these images, in particular Clay Afro.” In this image, she rests her head on her hands, face tilted slightly downwards but eyes looking up, and the object appears like a sort of crown. Akinpelumi adds that the choice of film was imperative to the project. “The black and white, and the grey tones of this work are all important. I’m exploring all the different ways I see myself and all the different ways I feel perceived.” It’s like a spectrum of identity she can select from in this way.

Akinpelumi spent her early life in Macclesfield, and back and forth between Manchester, splitting pockets of time between different family members. “I lived with my amazing mum, my older brother (sometimes), shared a bedroom with two of my sisters, and spent weekends with my dad, his girlfriend and three other siblings. Then when I started college in Salford in 2015, I had to start from scratch all over again. This was the real birth of me. Life in Macclesfield, with it being so sheltered, gave you room for you to make something out of nothing. I could set up events with 100+ people in my house and it was safe. I learnt to connect with people and create an atmosphere, and this has never left me. It feels inherent.”

From a young age, she always had an interest in fashion and a preoccupation with style and taste. “In essence, that’s creating an image for yourself, isn’t it? And now I am image-making. Photography followed me.” She studied textiles to begin with, but a real turning point came only in the past year, when she began having panic attacks related to the choices she had made thus far. “I knew something wasn’t aligned, and that I had to change to photography and I’m sure I’ll figure out why at some point. I trust my body. If it wasn’t for that, back in November, I wouldn’t be doing this interview.”

Akinpelumi says that compartmentalizing is something the media thrives on, and that’s hard because she represents the opposite of that. “I’m currently reading a book called Mixed/Other by Natalie Morris and it describes the experience of being dual-heritage perfectly,” she says. “When speaking about her heritage Morris says, ‘There is some inherent barrier of perception. Because, while I am allowed to be black like my dad, I am definitely not allowed to be white.’ I recommend this book as it shows multiple different stories which is definitely the way forward when speaking about race. We are still learning yet the media teaches us to fight for sides. Fight for one idea, believe it applies to all, and feeds us the side we want to eat. It makes our plates full, and gets us sick without realizing. We forget our internal selves, who we are as people, before controversy or before divide, as a friend, a person, or human being and this is what the media banks on.”

My narrative used to be that I was half of something and half of something else and until this project I’d never considered that I am also a whole. I am 100%, also.

She talks about Dichotomy being her chance to “establish a sense of recovery” through pictures, like self-healing in a creative way. “And when I say that,” she explains, “it’s because in the making of these images I had to recover feelings, dominant emotions I had in my childhood for various reasons, usually ones that are hard to describe. It’s also important to mention that initially starting the project and speaking of this 50/50 state made it seem as though I was unusual or had no sense of belonging. But the project unhinges this illusion as I’ve found that many people can relate to this feeling of not belonging anywhere, that there is community in that, and that ‘nowhere’ is a place in itself. My narrative used to be that I was half of something and half of something else and until this project I’d never considered that I am also a whole. I am 100%, also.” Through the act of taking pictures of herself, she could unite both parts of herself in one image to project out to the world.

Having photographed herself in such a concentrated way for the first time in this project, Akinpelumi surprised herself with how intimate and affirming the experience turned out to be. “I was in a very safe environment at the time which was probably really important in the making of this project. I could be me, myself and be free,” she recalls. “The emotions were completely intuitive; I made the equipment and then would turn the camera on myself and take myself back. It just required me to be honest and present, but the conditions of my environment, shielding in lockdown, and being used to having myself to myself, all had a part to play in being brave enough to be intimate. I had one rule for myself and it was to be real.”

Akinpelumi hopes that those looking at these pictures will take a sense of the truth—or her truth, as she tells it—from them. “Hopefully, for those that would never have asked, they’ll take an interest too, and hopefully to all those that feel in any state of in-between, they’ll see a friend,” she says warmly. The overarching themes of these images will always endure; family, belonging, heritage, identity and a little performance too—relatable themes that connect her to others and inspire conversations.

Meanwhile, when asked what, in her opinion, makes a powerful portrait, her answer is clear and concise. “It’s one that locks you in. One that makes you want to return,” she says, and each of her self-portraits embody this notion. With her gaze steady, she explores who she is with grace and emotion in front of the lens.